Insights

Market signals and shifts: What to watch in 2025

Our award-winning research team draws on State Street’s proprietary data to address pressing questions shaping global markets in 2025.

January 2025

Tony Bisegna

Head of Global Markets

Will Kinlaw

Head of Research, Global Markets

As we turn the calendar to 2025, investors have much to celebrate. Strong economic data and investor enthusiasm have propelled major indexes to record highs. However, stretched valuation ratios and geopolitical uncertainty underscore significant risks as does the December shift in the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy stance.

Through it all, institutional investors remain significantly overweight in equities. State Street’s investor holdings indicator reveals equity allocations at levels last seen on the eve of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Meanwhile, foreign investors have reduced the FX hedge ratios on their US dollar portfolios for the past three years exposing them to dollar weakness. A widespread dollar selloff could trigger a broader unwind of positions in risk assets.

These are among the key themes explored in Market signals and shifts: What to watch in 2025, a new publication from State Street Global Markets. In this edition, our award-winning research team addresses pressing questions shaping global markets today:

- Can the US and its tech sector remain exceptional?

- Will the US dollar’s strength persist?

- Is there trouble ahead for Treasuries?

- Has Europe already priced in bad news?

- Can China successfully reflate its economy?

Grounded in proprietary, data-driven insights, the answers to these questions provide critical investor guidance for the year ahead.

State Street’s global institutional investor indicators, leveraging aggregated and anonymized datasets, provide an unbiased view of actual investor behavior. These insights can reveal market shifts and turning points ahead of the broader narrative. As Michael Metcalfe, State Street’s Head of Macro Strategy explains:

“When investor attitudes finally waiver from optimistic extremes, they do so decisively and durably. Two notable examples of shifts in excessive equity optimism occurred in August 2000 and July 2007, after which investors reallocated away from equities for 31 and 21 months, respectively. These tipping points coincided with the worst equity drawdowns of the last quarter century, with declines exceeding 40 percent.”

State Street’s indicators can help investors stay ahead of tectonic shifts such as these.

In this publication, we also demonstrate how our media sentiment indicators gauge investors’ willingness to absorb longer-dated sovereign supply amid rising issuance and the implications for market conditions and government funding costs. Additionally, our new high-frequency PriceStats inflation indicators for China – derived from millions of online consumer price data points – offer early signals on whether China can avoid the looming deflationary trap in 2025.

These proprietary, data-backed insights are designed to help investors navigate the opportunities and risks in the year ahead.

Hear from Tony how our solutions can help give you an information edge.

Contents

- Asset allocation: Will investors remain overweight in equities in 2025?

- Can the US and US tech remain exceptional?

- Trouble ahead for Treasuries?

- Will US dollar strength persist?

- Europe: How much bad news is already priced in?

- Can China successfully reflate?

- Decarbonization: Divergence between the US and the EU grows

- Global regulatory trends to watch in 2025

1. Asset allocation: Will investors remain overweight in equities in 2025?

By Michael Metcalfe, Head of Macro Strategy

As we begin 2025, institutional investors are allocating a historically high percentage of their overall portfolios to equities. State Street’s indicators of institutional investor behavior are tracking a 25-year average allocation to equities that is 20 percent more than fixed-income securities, consistent with a traditional 60-40 equity bond allocation. But the current allocation to equities is a third higher than this and is at levels not seen since the financial crisis. So, what does that mean as we head into 2025?

In theory, equities may have run their course

Concerns that institutional investors are far too overweight in equities and underweight in bonds are not new. At least for the last two years, these concerns have been featured in market outlooks. Each time, bond market optimism has been undone by sticky inflation, robust growth or uncertainty about the short-term rate cycle. Equity markets have proven to be remarkably resilient, helped in part by US and tech fundamentals.

In theory, with central bank easing cycles now underway, 2025 should be a much easier call for asset allocation, both literally in terms of actual policy, and in the outlook for bonds. But in practice, investors may still need a good deal of convincing that sovereign bond markets are a better home for allocations than equities.

We could, however, have made a similar argument at the beginning of both 2023 and 2024, that allocations to equities were high relative to recent history. And, as we show in Figure 1, this should not be thought of as maximum optimism. Investors have actually had a higher allocation to equities in just under a quarter of our 25-year sample, specifically between 1999-2001 and 2003-2008. Given these periods were the run-ups to the dot.com bust and the Great Financial Crisis, respectively, some caution is probably required.

What is also clear in Figure 1 is that Fed easing cycles usually coincide with reallocation out of equities back to bonds. Over the three cycles seen during the past quarter century, investors on average moved 14 percent of their portfolios out of equities into bonds during regimes when the Fed was reducing interest rates.

Putting these together, we show that the allocation to equities has only been higher than it is today in the run-up to financial crises and, in theory, we have just entered a phase of the monetary cycle which typically sees equity allocations fall substantially. A coherent argument, it seems, for why 2025 should be the year of the bond and a riskier one for equity holdings.

But in practice, equities remain remarkable

There are three fundamental challenges with this argument in practice, many of which feature as specific factors to watch in our list of data for 2025.

First, overweight equities relative to bonds has been a somewhat counter-consensus winning trade for two years in a row now. Repeated warnings about positioning and concentration are beginning to sound like the boy who cried wolf.

Second, as crowded as US equities and tech holdings are, they are still, as we’ll discuss, supported by relative fundamentals. This is not expected to change in 2025 unless the consensus is very wrong on US growth or earnings.

Third, the sharp rise in longer-dated US yields following the beginning of the Fed easing cycle already suggests that this easing cycle may be somewhat different. Concerns about a more aggressive US fiscal expansion, potentially reduced labor supply due to changes in immigration policy and the imposition of universal tariffs could prove challenging for inflation expectations and term premia.

To conclude, aggregate equity allocations do look high and would typically be expected to fall from here, even more so given we are in the middle of a Fed easing cycle. Nevertheless, the recent history of remarkable equity resilience, specifically in the most crowded areas of the equity market combined with the anticipated changes in US policy in particular, means that this potential shift cannot be taken for granted in 2025. For perspective, the current upswing in institutional investor optimism toward equities began in March 2020 at the height of the COVID panic, so is approaching its fourth anniversary. It could yet make it to five.

What we do know is that when, or if, investor attitudes do waiver and eventually turn from such optimistic levels, they will do so both decisively and durably. The two historical examples of turns in excessive equity optimism in the past came in August 2000 and July 2007. Following these tipping points, investors subsequently allocated away from equities for the following 31 and 21 months, respectively, coinciding with the worst equity market drawdowns over the last quarter century with declines in excess of 40 percent.

With that precedent, we will be closely watching investor equity allocations relative to bonds, to gauge whether they follow the theory of mean reversion during Fed easing cycles, or the recent remarkable practice of equity resilience.

2. Can the US and US tech remain exceptional?

By Marija Veitmane, Head of Equity Research

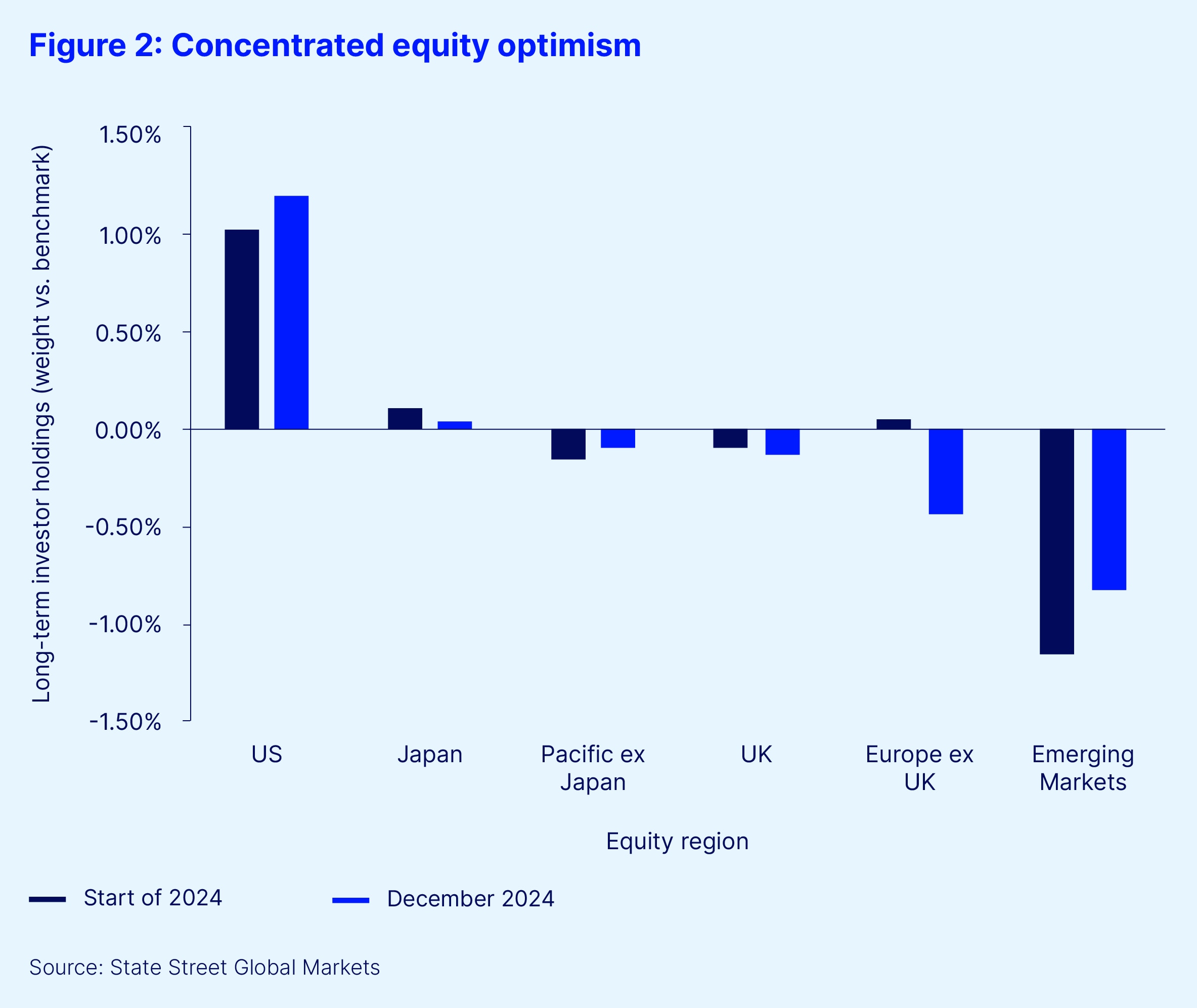

Not only is institutional investor allocation to equities at a historic high, but exposure is concentrated in US equities. And within US equities, it’s further concentrated in the tech sector. That means global investor attitudes toward the US and US tech stocks may hold a key to any reallocation of global investment portfolios.

State Street’s indicators of institutional investor behavior show that the US is the only market with an above-benchmark allocation, while institutional investors are underweight in every other region (Figure 2). The size of the US equity overweight position is also very significant – it was only higher in mid-2022 when the Fed was just embarking on its tightening cycle. What may be even more surprising is the fact that institutional investors have continued adding to their already overweight US equity holdings this year.

Some might argue, and indeed portfolio theory would, that this is an overly optimistic and potentially risky situation for institutional investors. However, the flight to ‘quality’ stocks (higher margins and return on equity, strong earnings growth and cash flow generation) indicates investors are prizing solid and stable fundamentals above all else.

Irrational exuberance or rational preference?

The key question for equity investors in 2025 is whether the momentum that propelled US stocks to all-time highs in 2024 can continue.

There are a number of tailwinds to consider. From a policy perspective, US President-elect Trump is promising tariffs, tax cuts and deregulation, which have the potential to improve the relative position of US equities from what was already a strong fundamental starting point. Once again, in 2024, US companies outgrew the rest of the world – their projected earnings growth for the year is nearly 10 percent while the rest of the world contracted. Nor is growth the only relative advantage. US stocks also offer a superior quality profile – higher margins / return on equity and stronger cash flow generation. So perhaps it is not completely irrational to crowd into safer, high-quality assets when concerns about potential economic and earnings slowdowns are at the forefront of investors’ minds.

What are investors buying in the US?

Within the high regional concentration in US stocks, our indicators show a substantial crowding into IT mega caps. On the surface this looks like an extremely risky position, as those stocks are trading at a substantial valuation premium both to the rest of the market and their own history.

However, once again, it is possible to argue that the IT sector represents a quality option for investors. IT (including communications) stocks tower over the rest of the market not only in size and performance, but also in terms of earnings growth. Indeed, nearly ALL earnings growth in the US stock market in 2024 came from tech stocks as they were able to use their market leadership position to maintain strong margins and profitability despite earnings slowdowns elsewhere.

So once again, a high allocation to the IT sector can be seen as crowding into expensive quality stocks.

Narrow rally expectation

Buying expensive quality stocks only makes sense when investors are concerned about a broader earnings slowdown and therefore need to pay up for more stable profits and margins. This is exactly what our indicators show institutional investors are doing now, despite all the talk about a soft landing for the US economy.

This suggests that investors continue to expect a narrow US / tech / large cap / quality-led equity rally. And this is our base case, as well.

But uncertainty surrounding policy, whether it be US interest rate, trade or fiscal, means that there are several potential other paths in 2025. For example, the US economy may not land at all, prompting a reassessment of cyclical sectors such as industrials or even materials. Or the economy may overheat to a point where bond market disruption – another factor on our watch list – pushes yields to levels that are challenging even for tech once again. In either case, institutional investor flows should give us a good indication of when or if their conviction in this highly concentrated momentum trade begins to waiver. All we know for sure is that holdings are such that it will likely take weeks if not months to unravel, giving an early warning sign of potential equity market turbulence.

Hear from Will Kinlaw on the market intelligence we gain from our Institutional Investor Holdings Indicator.

3. Trouble ahead for Treasuries?

By Hope Allard, Macro/Multi-Asset Analyst

Market and media focus on the US election brought debt sustainability fears to the surface this year, as neither presidential candidate seemed likely to prioritize shrinking a federal budget deficit currently projected to remain upwards of 6.5 percent of GDP (relative to a 3.7 percent historical average).

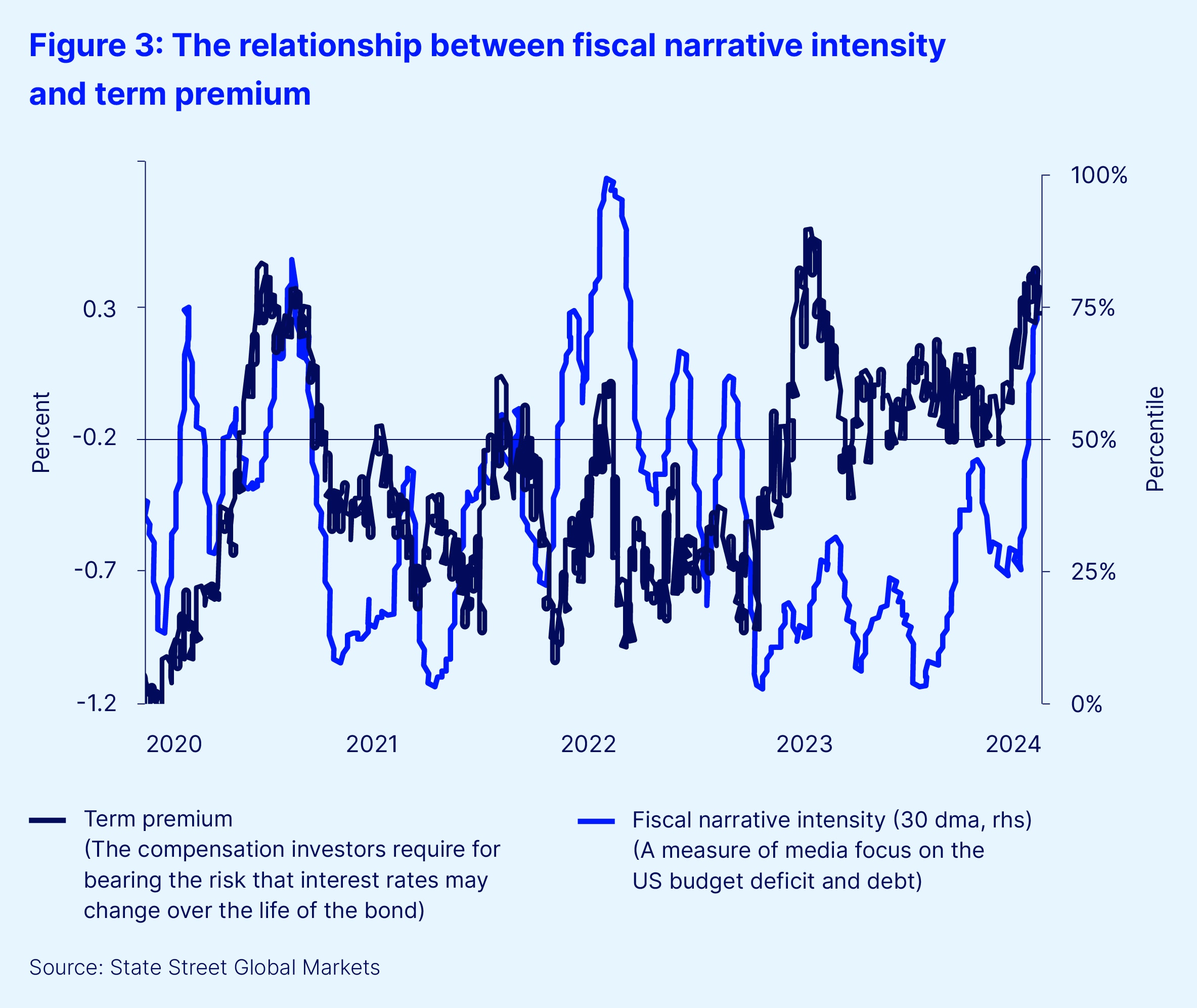

These developments led to intensified media coverage of the fiscal outlook, putting upward pressure on term premiums (the compensation investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond) which took a notable turn higher as the prospect of increased spending rose with the odds of a red sweep. Such concerns ultimately saw 10-year Treasury term premiums push into positive territory at the start of October and they have remained there ever since.

While term premiums have become volatile post-election, the ongoing relationship between media focus and the required compensation for owning duration is emblematic of the market’s sensitivity to the US deficit and debt dynamics (Figure 3).

Debt: Still on the watch list

While the US election brought fiscal concerns to the surface recently, debt sustainability has been on our watch list for the last few years. Moreover, it also features prominently on the Fed’s watch list, as the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) recently flagged debt sustainability as the primary risk to financial stability, given the potential that elevated Treasury issuance can crowd out private investment and/or limit fiscal policy responses.

Kansas City Fed President Schmid also cited running large deficits as a reason for the Fed to maintain higher rates in the coming years. With investors questioning the depth and pace of the Fed’s easing cycle, as well as where rates will eventually settle post-pandemic, who the marginal buyer of increased Treasury issuance will be and, what it means for yields, remain key questions in our minds for 2025.

Who will be the marginal buyer?

Treasury demand among historically large cohorts of foreign buyers, including foreign governments and central banks in Asia, along with oil-exporting countries, has diminished of late due to factors ranging from changes in trade balances to shifting reserve management practices.

The Fed has also been a prominent player in the Treasury market as it “twisted” its portfolio by buying longer dated securities, thereby draining duration from the market. However, with the current round of quantitative tightening entering its third calendar year, it suggests to us that the Fed may target a smaller and lower-duration balance sheet going forward.

This leaves domestic private investors (including real-money institutions) as the marginal buyer going forward, a cohort that has already notably increased its holdings since issuance surged in 2022. This shift effectively requires greater participation from price setters at the expense of price takers, potentially raising term premiums and government borrowing costs by extension.

Based on our analysis rooted in existing holdings, overall yields and macro-economic influences, we see scope for this evolving ownership structure to add as much as 95 basis points of additional term premium on long-end yields as issuance increases.

Is weak demand really cause for concern?

Our indicators of institutional investor behavior also support the idea that institutions will require greater compensation for holding supply at the long end, with real-money investors selling 30-year US Treasuries since September, the longest stretch of outflows since the first half of 2020.

While shorter-dated Treasury flows began to signal improvement in demand throughout October on the back of firming expectations for fewer Fed cuts over the next year, the 30-year sell-off only grew more aggressive despite already underweight positioning.

This points to a reluctance among real-money institutions to increase their exposure to the longer end of the curve, with US fiscal responsibility increasingly in question.

Real-money Treasury demand by key maturity is therefore something that bears watching as we gauge alternative buyers’ willingness to absorb longer-dated sovereign supply amid increased issuance, and what it ultimately means for both market conditions and government funding costs.

4. Will US dollar strength persist?

By Lee Ferridge, Head of Macro Strategy, North America

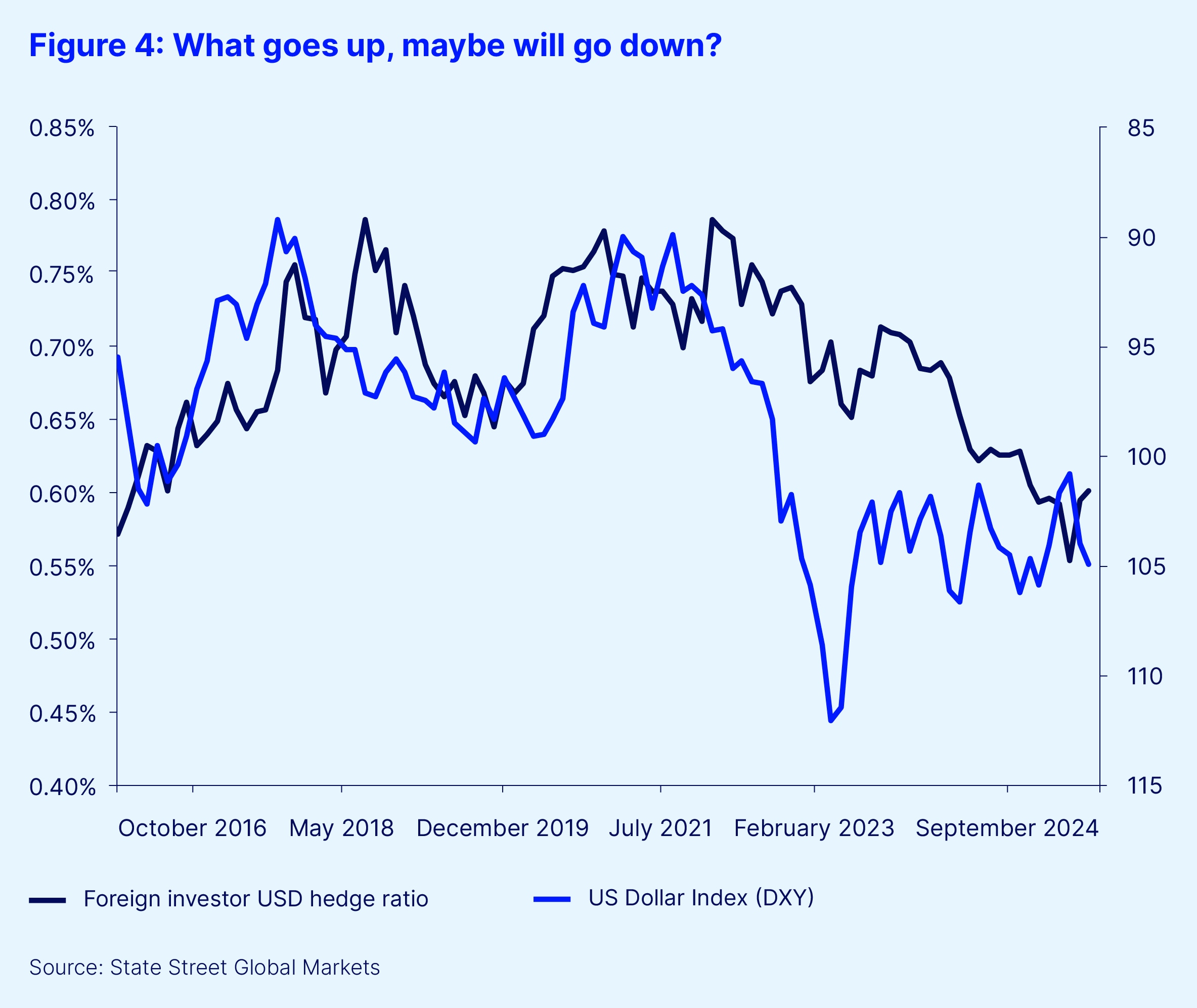

Foreign investors have spent the last three years reducing the FX hedge ratios on their US dollar (USD) asset portfolios. From a peak level (averaged across Equity and Fixed Income portfolios) of close to 79 percent reached in late September 2021, the hedge ratio recently hit 55 percent, its lowest reading in over 8 years. This leaves foreign investors heavily exposed to dollar weakness and hence, should the USD start to falter, could lead to a prolonged decline as foreign investors rush to boost their hedge ratios (and thereby sell the USD).

As Figure 4 illustrates, there is a strong inverse relationship, as one would expect, between the level of the foreign investor USD hedge ratio and the USD itself. As hedge ratios fall (and hence there is less forward selling of the USD), so the dollar gains. Since the hedge ratio peaked in September 2021, the US Dollar Index (DXY) (the value of the USD against a basket of currencies) has risen by over 13 percent.

What drives hedge ratios?

A key question for 2025 therefore is whether the USD is indeed likely to falter and thereby trigger a more prolonged (and pronounced) USD downtrend as hedge ratios are rebuilt. To answer this, we need to understand what has driven the downward trend in the foreign investor appetite to hedge their USD exposures. The answer is relatively straightforward – relative interest rates.

There is a strong relationship between the level of US short-term rates and foreign investor appetite to hedge US dollar exposures. Quite simply, as it becomes more expensive to hedge the FX exposure of their US assets, foreign investors are less inclined to sell dollars forward. So, as is so often the case, the outlook for the dollar becomes inextricably linked to the path of US interest rates.

What the multi-year low in the hedge ratio does is make the stakes for the dollar still higher. Any weakness is likely to be exacerbated by such extremely current low levels of hedging as USD weakness will trigger hedge ratios to be rebuilt, leading to fresh dollar selling and, thereby, causing more investors to rebuild their own portfolio hedge ratio as the dollar declines. A virtuous circle of dollar buying over the last three years could easily turn into a vicious circle of dollar selling.

Trump is good for dollar bulls

Luckily for the dollar bulls, the recent election result and anticipated policies from the second Trump administration look set, all other things being equal, to increase inflationary pressure in the economy, at least as we look through 2025, and thereby maintain (or even increase) the level of relative US rates. Trade tariffs, further fiscal loosening and the proposed clampdown on immigration (and, perhaps, significant deportations) are all likely to increase price pressures to some degree. This has already started to be reflected in more medium-term rate expectations.

So, the circle is somewhat complete. Relative rates drive the hedge ratio, and the hedge ratio drives the medium-term US dollar direction. So long as the level of relative rates remains elevated in favor of the US, then the downtrend in foreign investor USD hedge ratios is more likely to persist than to reverse.

Hence, if the proposed Trump polices are enacted as promised and, should they prove as potentially inflationary as the vast majority expect, then the USD should continue to receive support from investor flows in 2025 and hence, its gains will persist. This is always the case, of course, it is just that with hedge ratio levels already at multi-year extremes, the stakes in 2025 for the USD are significantly higher than usual.

5. Europe: How much bad news is priced in?

By Tim Graf, Head of Macro Strategy, EMEA

It is hard to find good news about European economics or politics. Rapid monetary tightening needed to curb post-pandemic inflation has done its job in bringing inflation back to the European Central Bank’s (ECB) target of 2 percent. But it has done so with the usual cost: slower domestic growth and a weaker outlook.

China’s continued efforts to recharge and reorient their economy away from investment-driven growth toward the consumer makes for weak demand for European exports, which is also taking a toll.

And, similar to the debt crisis years of the early 2010s, the currency union looks plagued once again by political volatility, anxieties over fiscal deficits and rising debt levels. Worryingly, the concern now comes in core countries – France, most notably – rather than the peripheral countries which saw such extreme volatility 15 years ago.

Many of these negatives have already been taken into account by investors. Eurozone equities underperformed their US counterparts by more than 15 percent this year, even more when considering the weakness of the euro. The EURUSD exchange rate is currently at two-year lows, and in recent weeks the spread of 10-year yields in France versus Germany increased to the widest levels in more than 10 years.

With ECB policy rates priced by interest rate markets to fall more than any other G10 economy in 2025, underscoring the weak outlook and removing even further rate support for the euro, it begs the following questions: How much further weakness can these trends accommodate? And how much more can positions adjust to the troubling realities of weaker growth and political uncertainty?

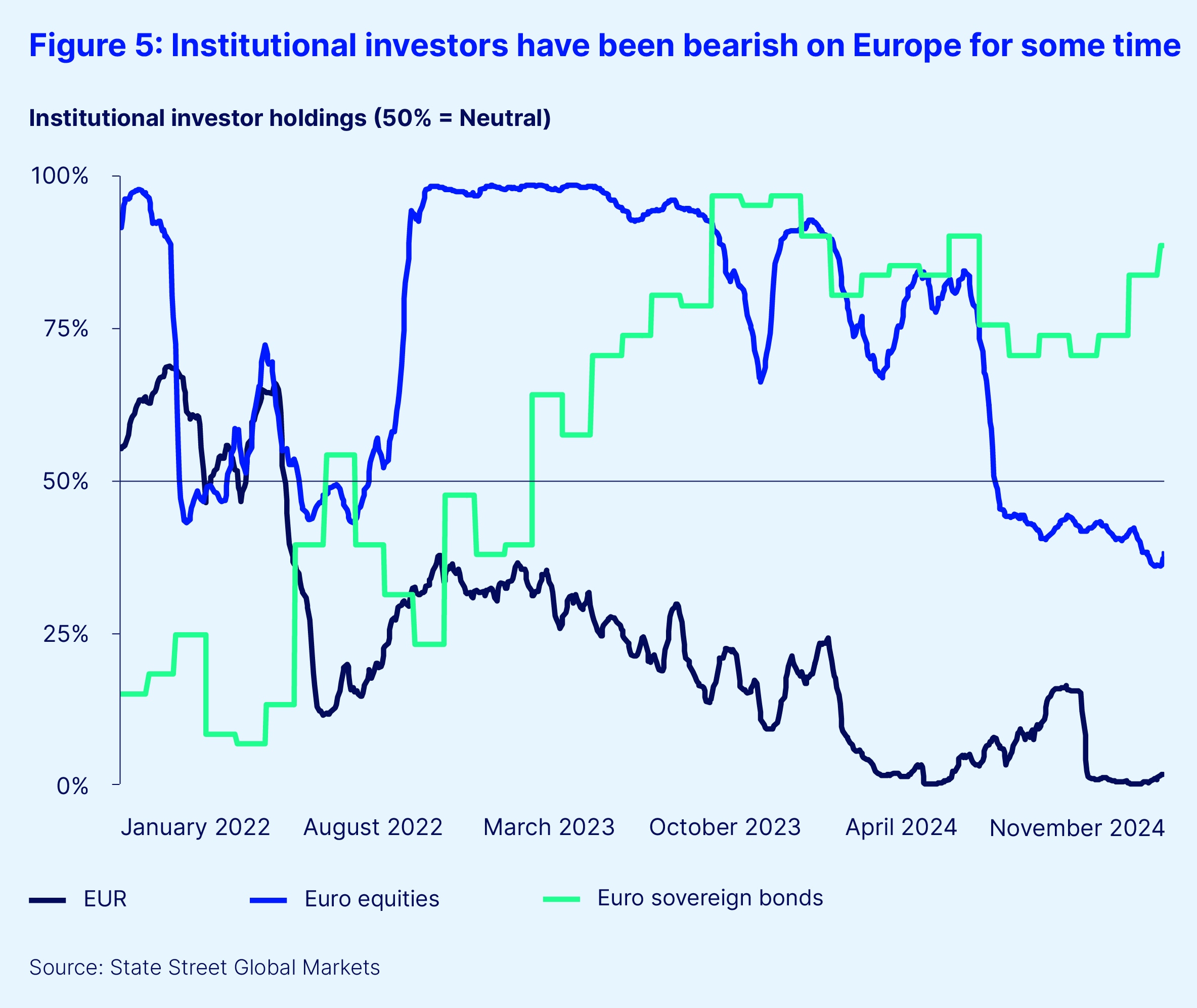

Our metrics of institutional investor holdings of the single currency and Eurozone assets offer guidance on the second question. Below we show five-year percentile positions relative to benchmark for major European markets (Figure 5). A considerable amount of risk has already been taken. In early summer, investors in European equities rapidly unwound an overweight that had been in place for more than a year and continue to build an underweight.

The shift in the ECB’s policy cycle across 2023 and 2024, from tightening to neutral to easing, was well-anticipated by fixed-income investors, as holdings of Eurozone government bonds rose to five-year record highs a year ago, near where they remain today.

Finally, and most poignantly, the euro itself has fallen out of favor with institutions. Investors have been underweight in the euro for more than two years. The current deviation from benchmark is one of the largest such positions observed, exceeded only by the worst stages of the 2010-2011 Eurozone debt crisis.

But bearish sentiment may not have run its course. The equity underweight is still modest and many of the themes of US exceptionalism expressed elsewhere in this document leave European shares wanting in comparison. Sector composition alone puts European equities at a disadvantage, given the lack of large cap information technology exposure that we continue to see appealing to investors in 2025.

While it is less likely that EUR underweights grow beyond the current extremes, we would note that valuation is not as binding a constraint for a weaker euro. The bilateral purchasing power parity-based valuation for EUR/USD derived using data from PriceStats, (our high-frequency indicators derived from millions of consumer goods prices gathered online) shows the euro as only 4 percent undervalued. This is not an especially extreme exchange rate misalignment. Only two years ago, when the dollar index reached its highs of the previous 20 years, this valuation gap was as wide as 30 percent, with EUR/USD 10 percent weaker than current levels.

Finally, should the mixture of political volatility and debt dynamics become more toxic, the positioning in European sovereign bonds is a potentially underappreciated vulnerability. Should the growth concerns that sparked a build-up of positions give way to credit concerns, there is considerable scope to sell, likely to the detriment of other European assets and the currency as well.

At time of writing, Eurozone sovereign bond flows are among the weakest in the world, suggesting institutions may already be thinking ahead about this particular risk. And it will take time for the effects of policy easing already offered to take hold and improve domestic fundamentals. And so, in the case of Europe, we find very little evidence to disagree with the current bearish market consensus.

6. Can China successfully reflate?

By Yuting Shao, Macro Strategist, Emerging Asia

In 2024, it seemed as if China’s post-COVID reopening could provide an extra boost to global growth, supplementing ‘US exceptionalism’. The reality was much more disappointing.

China’s post-COVID reopening, with its aging demographics, property downtrend and heightened deflationary risks, drew parallels to the ‘Japanification’ narrative where the continued underperformance in recovery could weigh on confidence, creating a vicious deflationary spiral. Given what growth China did deliver in 2024 was heavily (~40 percent) reliant on exports, the outlook for 2025 could be even more challenging.

While details of the new Trump administration policies are still uncertain, US tariffs on Chinese exports look set to rise, bringing additional external headwinds to the already struggling outlook. This will place even more pressure on a proactive policy response from the Chinese authorities.

There was already some evidence of this in the second half of 2024. Beijing rolled out various pro-growth packages starting in late September, including monetary policy easing, support to housing and equity markets, alongside fiscal support to address local debt problems. This was warmly welcomed by a dramatic turnaround in financial (and, in particular, stock market) sentiment. So just as 2023 ended with hopes about the potential for growth in the following year, so, too, did 2024. But for this optimism to be sustained, an improvement in the real economy will be needed.

Signs of life in the real economy?

Considering the usual lag of policy transmission through to the real economy, it is still too soon to expect traditional economic data to show meaningful improvement. But we know where to look. It is evident that stringent COVID-era policies had a long-lasting impact on the jobs market, income and spending patterns, while the property sector downturn has weighed on household wealth. As a result, the lack of sustained consumption recovery has brought the risk of entrenched weak confidence. Observing this, retailers have not felt confident enough to raise prices and the economy has remained stuck in, or near, deflation. There are, however, some green shoots beginning to emerge in some faster moving measures of inflation.

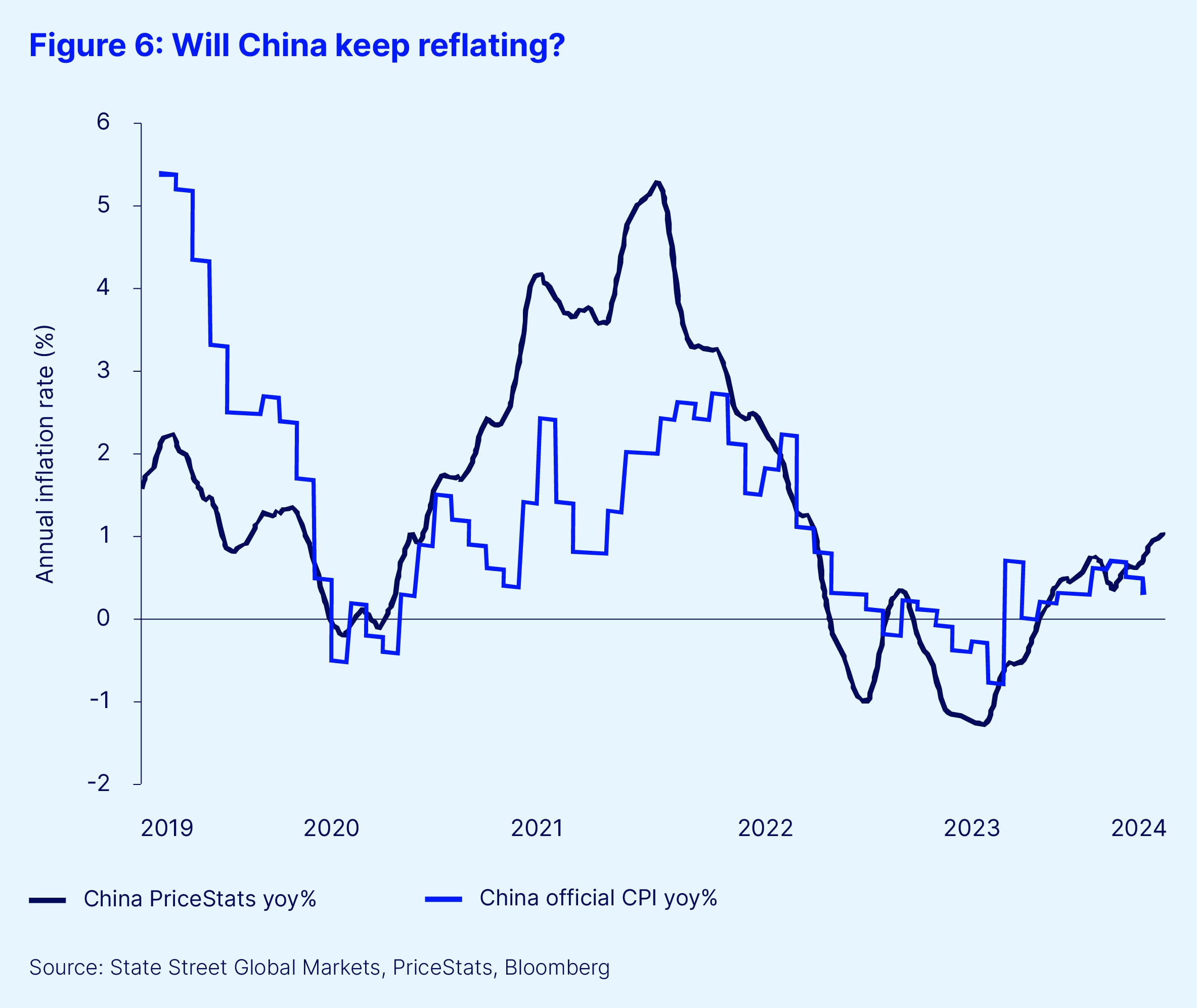

China’s online prices, the latest of our expansion of PriceStats indicators, while trending up in recent months due to the low base from last year, still show relatively subdued domestic demand. This underscores the lack of consumer willingness to increase spending despite the policy combination of late (Figure 6).

Nevertheless, online prices are beginning to trend upward once again and are now approaching 1 percent year on year; their highest reading since the reopening. This, along with scattered evidence of firmer retail sales, could be evidence that retailers are beginning to believe consumer demand is firm enough to once again sustain higher prices and inflation.

But it’s still early days. Just as hope of a stronger, reopened China was dashed in 2024, so it could be again in 2025. We will be closely monitoring the latest trends and developments in our high-frequency Chinese PriceStats series to gauge whether the Chinese authorities have done enough to stabilize growth in the face of stronger external headwinds or whether further stimulus is needed to avoid slipping back into deflation once more.

Potential growth boosting policies in 2025

There are plenty of forms this policy stimulus could, and likely will, take in 2025. For the domestic economy, it’s vital for monetary policy to stay accommodative – more policy rate/RRR cuts are needed to ensure ample liquidity. The National People’s Congress meeting in March will likely release key targets for 2025, including growth, budget deficit etc. We expect a GDP target of around 4.5 percent and the central government to expand the budget deficit supported by additional special sovereign bonds and local government special bonds. The increase in direct transfers of revenue and purchases of unsold units should alleviate the drag from the property sector. For the consumer, more counter-cyclical policy measures, including subsidized goods purchases, tax breaks and rebates to households and corporates should increase the fiscal multiplier and build a better social safety net.

As in September 2024, the knee-jerk stock market reaction will be one gauge of the impact of these additional stimuli on financial market sentiment. However, once again their ultimate success in terms of the real economy will be judged by whether it encourages retailers to raise prices. The risk is that China fails to escape the deflationary trap it could so easily fall into in 2025.

7. Decarbonization: Divergence between the US and Europe grows

By George Serafeim, Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and Academic Partner at State Street Associates and Alex Cheema-Fox, Head of Investor Behavior Research, Sustainability Research, State Street Associates

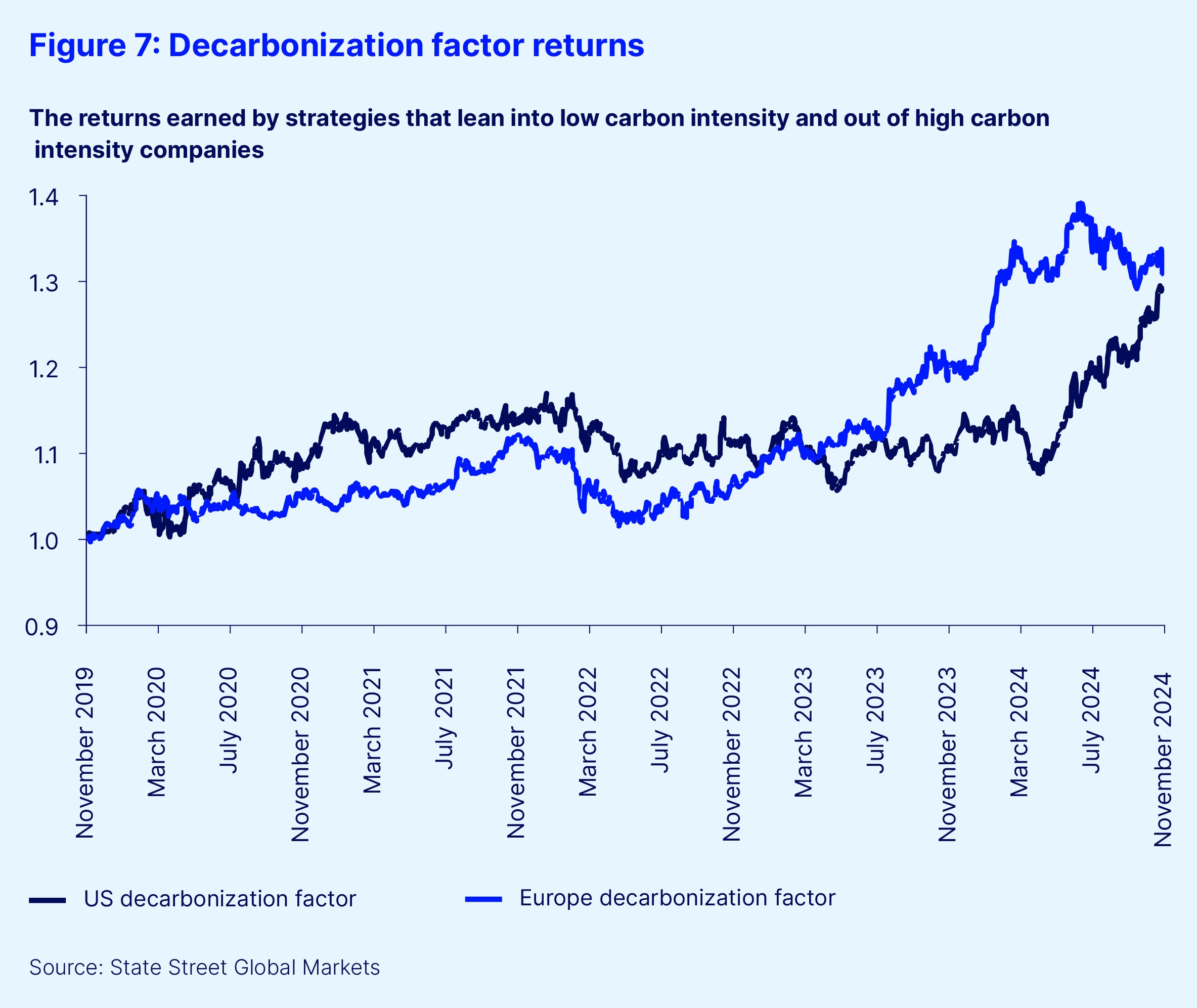

Over the past year, there’s been a divergence in performance between US and European decarbonization strategies (Figure 7). State Street’s Decarbonization Factors, based upon our published research, are constructed to track the returns earned by strategies that lean into low-carbon-intensity companies and out of those with high-carbon intensity.

On average, returns to these strategies have been positive over time, but there are differences across countries and time periods. European decarbonization returns soared early in 2024, while the US saw some retrenchment before catching up from summer onwards. While the US decarbonization factor return is similar to the S&P 500 index year to date (as of late 2024), the European decarbonization factor has exhibited stronger performance than the analogous STOXX 600 index.

As we head into 2025, institutional investors should keep a close eye on several pivotal developments shaping decarbonization efforts and investment opportunities. Here’s what to watch:

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): Dead or alive?

Should the Trump Administration repeal the IRA or parts of it, we would likely see headwinds for the US decarbonization index, as decarbonization technologies would have less policy support and could become more expensive. This could lead some companies to abandon their efforts or to face cost inflation in their production process which, in turn, they could pass to their customers (with implications for revenue growth) or absorb in their profitability margin. Conversely, if the IRA continues intact and the Trump Administration reduces bureaucracy and expedites deployment of funds, we could see tailwinds for the US decarbonization index.

“Drill baby drill”

President Trump has called for increasing oil production and lowering prices. Should he be successful in pushing oil supply up, this will (counterintuitively for some) provide tailwinds for the US decarbonization index. Lower prices mean lower profit for energy companies, an industry underweight in the index given its high-carbon intensity.

Strength of the European economy

If Europe’s economic activity picks up, we expect a positive impact on European Union Emissions Trading System prices and the European decarbonization index through cost inflation for high-carbon producers. This, coupled with the coming carbon border adjustment tax, would place low-carbon producers at a place of relative competitive advantage for sales within the EU block.

Inflation and interest rates

The faster interest rates come down the better (on average) for climate technologies and therefore the more cost-effective decarbonization. Technologies, such as renewable energy are heavy on upfront capex and low on ongoing operating expenses (relative to fossil fuels generation) and are therefore negatively affected by increases in interest rates. Taming of inflation and faster reductions in interest rates could provide tailwinds to the decarbonization indices.

China

There is increasing skepticism on both sides of the Atlantic about China’s trade practices. Tariffs and bringing back home production are on the table. China is the undisputed champion of decarbonization technologies. Due to economies of scale and learning, it has brought down the cost of those technologies. Protectionist policies, such as tariffs or reshoring production, could swing outcomes either way.

On one hand, these measures may increase the costs of decarbonization technologies for companies dependent on Chinese suppliers. On the other, they could boost domestic manufacturers in the US and Europe by reducing competition, fostering local production, and supporting regional supply chains.

The bottom line

For institutional investors, 2025 promises to be a year of complexity and opportunity in the decarbonization space. Whether navigating geopolitical tensions, shifting regulatory landscapes, or macroeconomic pressures, the interplay of these trends will shape both risks and rewards in the journey toward a low-carbon future.

8. Global regulatory trends to watch in 2025

By Joseph Barry, Global Head of Public Policy and Sven Kasper, International Head of Regulatory, Industry and Government Affairs

When it comes to government policy impacting the global financial industry, 2025 is shaping up to be anything but business as usual. A new administration in the United States that is poised to rewrite regulations across the board, newly composed EU institutions and political uncertainties in Europe, ongoing changes in China’s economy, and global tensions at the highest level since the Cold War make up a shifting landscape for financial services.

At State Street, we’ve identified three major trends that may provide a useful framework for keeping abreast of global regulatory developments in 2025. These include:

1. Increasing regulatory divergence across jurisdictions

The incoming Trump Administration in the United States is expected to pursue a deregulatory approach, but with an anti-ESG/climate risk agenda and a preference for bilateral engagement rather than participation in multi-lateral organizations. There are a number of implications from this approach. First, we would expect to see reduced global cooperation and coordination through multi-lateral organizations such as the Basel Committee, Financial Stability Board, and International Organization of Securities Commissions. Second, there may be potential pressure from the US on the EU to eliminate the extraterritorial reach of EU rules, particularly around climate and sustainability.

ESG and climate risk regulations stand out as an area of increasing divergence. In the US, we expect a strong anti-ESG/climate/DEI focus across the government, starting with internal mandates to government agencies followed by a focus on government contractors and regulated entities. For the asset management industry, we expect heightened questions around the impact of ESG investment principles and a shift away from mandated disclosures of climate risk.

At the same time, the EU is continuing to standardize sustainability disclosures with companies in scope of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) reporting for the first time in 2025 on 1,000 ESG indicators where material. Additionally, there are the requirements from the Sustainability Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and additional requirements for funds’ names using ESG or sustainability terminology that came into effect for new funds in November 2024 and will come into effect for existing funds in May 2025. As a result, the gap between the EU and US will widen around sustainability rules, increasing complexity and costs for global firms.

Other areas of potential regulatory policy divergence include bank capital rules. There could be a reconsideration of the Biden Administration approach to Basel 3 Endgame capital rules. Over time, a revised, capital-neutral proposal seems likely, but complete abandonment of the Basel process is also possible. Then there are regulations around cybersecurity/operational resilience of financial firms and issues of data privacy which the EU is focused on and affect firms doing business in the region.

2. Regulations that may impact capital allocation decisions

Regulations in the US and EU around different asset classes could open the way for significant shifts in asset allocation among institutional and retail investors. For example, in the US, we expect a far more accommodating SEC view on crypto and private markets products and in the EU, we see continued focus on encouraging and attracting retail investors into capital markets.

In the US, we expect a strong pro-crypto shift across government agencies, particularly the SEC, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and banking agencies. And it is likely that the SEC’s current stance to prohibit bank custody of digital assets will be reversed. However, it remains to be seen whether the new administration’s overall approach amounts to a complete deregulation of crypto firms or a new regulatory regime.

In the EU, the impact of critical regulations such as Markets in Crypto-Asset Regulation (MiCAR) will be felt in 2025 as the framework to standardize key regulatory principles for crypto companies across the EU is put into practice and enforced by individual member country regulators. Other regulations that will impact crypto firms include the Transfer of Funds Regulation (TRF) and the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). EU regulators are also looking into the potential of central bank digital currencies, while in the UK stablecoins are being considered by regulators. In APAC, China and Japan have been focused on stricter regulations on cryptocurrencies and that is likely to continue in 2025.

In private markets, the European Commission’s (EC) 2024 amendments to the European Long Term Investment Fund (ELTIF) rules have the potential to significantly increase both the volume and source of capital flows into European private markets in 2025.

3. Regulations around data and artificial intelligence

The EU continues to lead on regulatory efforts around data, data privacy, and technology that may have implications for the rest of the world, especially if global firms operating in the EU are in scope. In 2024, the EU published the EU Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act, the first comprehensive regulation around AI anywhere in the world. And it also has a digital action plan that includes the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, and the Data Act.

In 2025, the EU’s Data Act will come into effect on September 12, establishing rules for data access, switching cloud providers, and interoperability across the EU. It focuses on user rights and fair data sharing practices while still protecting personal information and will likely have a significant impact on how firms handle data in the EU.

The introduction of ChatGPT and the advent of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) heightened global attention on AI regulations in 2024 with several countries, including the EU, proposing AI frameworks to promote fair competitive practices. Regulators from the US, UK and the EU issued a joint statement outlining concerns about market concentration and anti-competitive practices in GenAI: “Given the speed and dynamism of AI developments, and learning from our experience with digital markets, we are committed to using our available powers to address any such risks before they become entrenched or irreversible harms,” the regulators noted, emphasizing the need for swift action in a rapidly evolving landscape.

Although the US, UK and EU authorities are unlikely to create unified regulations in the near term (especially with a new Administration in the US), their focus could lead to closer scrutiny of AI-related mergers, partnerships, and business practices in the coming months.

Conclusion

While much of the Trump Administration’s detailed regulatory agenda is still to be determined, several key takeaways are already apparent from the shifting global regulatory landscape in 2025. First, given the EU’s focus on retail investors and the US’s likely focus on encouraging retail investment in crypto and private assets, we see 2025 shaping up as a year of new investment opportunities for retail investors. Second, given the potential divergence in regulatory postures between the EU and the US around ESG/climate, banking, and data, we see an increase in complexity and costs for global institutional investors. Third, due to the acceleration of deglobalization and regionalization, we see a focus on increasing the competitiveness of capital markets particularly in the UK and EU, but also in APAC.